When individuals with intellectual disabilities approach the end of their lives, what they need most is not the cold presence of medical equipment, but the comfort of familiar surroundings and the warmth of trusted companionship. In recent years, Chiayi Francis Home and Changhua County Erlin Happy Christian Home have begun exploring how palliative care can be practiced within residential care facilities. Moving beyond the fear caused by unfamiliar hospital settings, and gradually building interdisciplinary care teams within their facilities, these institutions—guided by courage and faith—are creating the possibility for residents to spend their final days in a place they can truly call home.

In Taiwan, most palliative care still takes place in hospital wards. For people with intellectual disabilities, however, unfamiliar environments are often more frightening than physical suffering itself. In response to the natural course of aging, illness, and death, a small number of institutions have begun offering "home-based palliative care" within their facilities.

Among these pioneers are Chiayi Francis Home and Erlin Happy Christian Home. Many of their residents have lived there since childhood, spending decades with their caregivers and peers, and have come to regard the institution as their home. When death approaches, these facilities choose not to send them away from their familiar environment, but instead allow them to complete the final mile of life at home, accompanied by caregivers and peers.

Unfamiliar Hospital Wards Take Away a Sense of Safety

"For people with intellectual disabilities, unfamiliar hospitals can be even more frightening than the illness itself," reflected Hui-Tang Tsou, former Director of Chiayi Francis Home (now Executive Director of disability service institutions under the Catholic Diocese of Taichung). In the past, when residents' conditions worsened, they were typically transferred to hospitals for end-of-life care. Yet for many, this sudden change of environment caused deep distress.

"In the hospital, they face constantly changing medical staff, cold surroundings, and the loneliness of being unable to express themselves," Tsou explained. He recalled a cheerful and independent young man who, after being diagnosed with cancer and hospitalized, begged every day to return to the institution for a simple reason: "That's where the nuns and caregivers he knew were."

For these residents, Tsou emphasized, a sense of safety is often more important than treatment itself. Because they cannot always express their fear in words, their restlessness and anxious glances become the clearest cries for help.

Even brief environmental changes can have a powerful impact. Tsou noted, "Each summer, when the facility undergoes disinfection and residents must return home or stay temporarily in another institution, even a two-week separation can lead to emotional instability—and in some cases, a higher mortality rate." These experiences led Francis Home to realize that truly protecting residents in their final journey means allowing palliative care to take place in the setting they know best: their own home within the institution.

A Courageous First Step

In 2015, Francis Home began exploring palliative care within the institution, with a young resident diagnosed with terminal cancer becoming their first case.

Tsou acknowledged that, at the time, the facility lacked both the knowledge and equipment for end-of-life care, leaving staff anxious and uncertain. Yet driven by the resident's strong wish to remain in the home, the team held what Tsou called a "painful meeting." "We were confronting the unknown—deciding whether to courageously accompany him through life's final stage within the institution."

courageously accompany him through life's final stage within the institution."

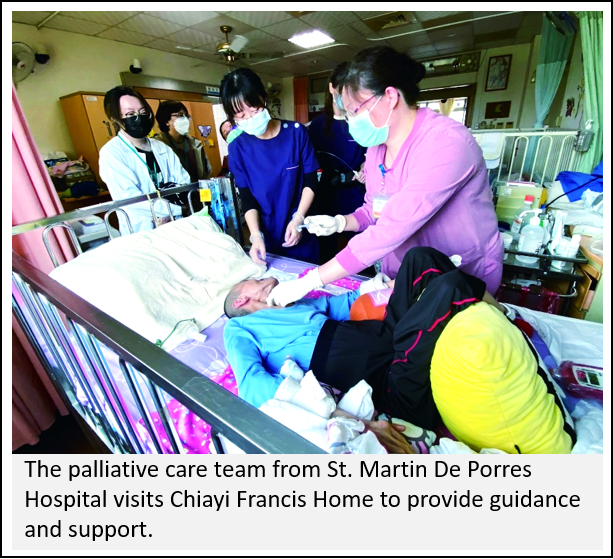

Ultimately, they chose to "take on the responsibility." The home invited the palliative care team from St. Martin De Porres Hospital, a long-term partner, to provide support while also training internal staff. The nuns, many with nursing experience, took the lead in caregiving, modeling care for the other staff to follow.

"At first, many colleagues resisted—it is a tremendous weight to bear," Tsou recalled. "But our supervisors stepped forward first, and gradually, fear gave way to action."

Following the resident’s peaceful passing, the team gained both confidence and practical experience: learning how to gently touch sensitive skin during bathing, how to calm anxiety with words and smiles, and, importantly, understanding "what not to say." Tsou recounted once remarking, "You’ve lost so much weight," only to see the resident's expression instantly change. He realized that the resident had not yet come to terms with their declining condition, and that even seemingly casual comments could cause emotional pain.

From One Courtyard to Society at Large

The palliative care journey at Francis Home did not start with a fully developed system—it began with a single resident's wish to "go home." That simple desire inspired the team to build an in-house palliative care program from the ground up.

Tsou notes that many institutions in Taiwan still operate with a "just send them to the hospital" mindset, lacking both the willingness and resources to accompany residents through life's final stage. He believes that government policies and incentives are needed to encourage facilities to honor residents' right to "grow old and pass away at home."

At Francis Home, palliative care is more than a medical service; it is a practice of human rights and dignity. Supporting residents to spend their final days in a familiar environment reflects the institution's commitment—and sends a broader message to society: the end of life should not be defined by the cold sterility of hospital wards, but by the warmth and companionship of home.

Erlin Happy Christian Home shares a similar approach. Its history reflects the broader evolution of disability care in Taiwan: from initially serving children with polio to later supporting individuals with intellectual and multiple disabilities.

"Our residents are getting older," explained Esther Lin, Superintendent of Erlin Happy Christian Home. Of the 198 residents, 57 are over 45 years old—nearly 30 percent of the population—and more than 100 have lived at the institution for over two decades.

These figures highlight a dual challenge: residents are entering high-risk stages for aging-related illnesses such as cancer and heart failure, while their families are also aging and less able to provide care. Consequently, death and palliative care have shifted from abstract medical concerns to unavoidable daily realities.

In 2018, Erlin applied to the Ministry of Health and Welfare to establish an "Aging Care Unit," reorganizing space, staffing, and daily routines. By placing nursing staff at the forefront of daily care, the institution was better prepared when its first terminal cancer resident reached the end of life in 2019, marking the beginning of its structured palliative care practice.

Care Centered on Fulfilling Final Wishes

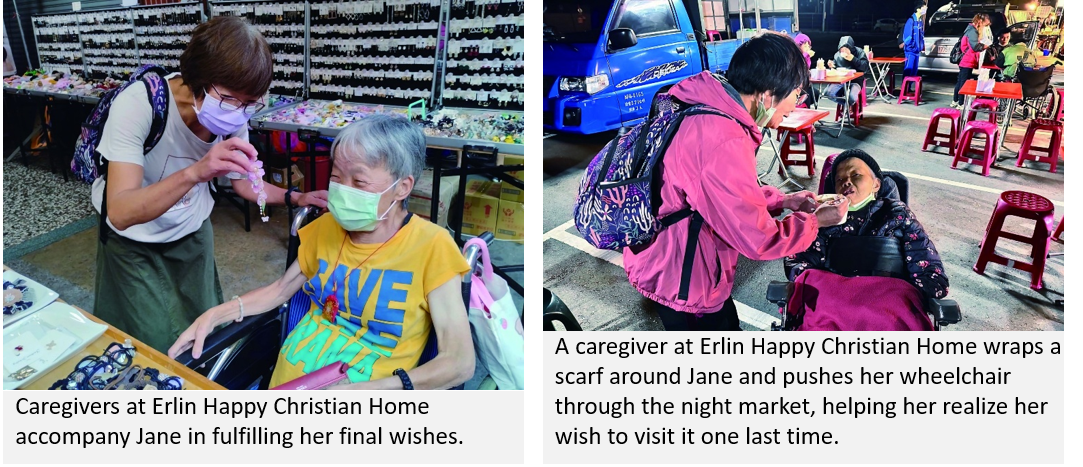

Jane's story is one of the most profound chapters in Erlin Happy Christian Home's palliative care journey. She had lived at the institution for over 20 years, and in 2023, she was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. Tumors occupied two-thirds of her liver, and doctors cautioned that she could pass away at any moment.

An interdisciplinary team—comprising caregivers, nurses, social workers, and a pastor—launched a Person-Centered Planning (PCP) process. Despite Jane’s limited cognitive abilities, the team made a concerted effort to listen to her wishes.

"She wanted to buy beautiful jewelry, enjoy oyster soup, and go shopping with her daughter," recalled Heng-Yu Tian, Team Leader of the Nursing Care Department. Caregivers pushed her wheelchair through bustling markets to savor the hot soup, and accompanied her and her daughter as they picked out new clothes. These seemingly simple moments brought light and joy back into her fading life.

As her condition worsened, Jane became restless at night, often crying between 1 and 3 a.m., saying she saw deceased relatives and friends. Through prayer and pastoral support, her emotions gradually calmed, bringing comfort to both her and the staff.

On the night before she passed, despite the cold weather, Jane insisted on going to the night market for a bowl of vermicelli soup. Wrapped in a scarf and surrounded by caregivers, she smiled like a child as she ate. The next day at noon, she passed away peacefully in her sleep.

"Though it was challenging, we are grateful to Jane," Tian said. "She taught us how to help someone with intellectual disabilities leave this world with dignity and fulfillment, even with limited resources."

Systemic Gaps That Constrain Palliative Care

Despite these experiences, institutional palliative care continues to face significant systemic barriers. Yi-Lin Kuo, Professional Associate Dean, highlighted the most urgent issue: insufficient medical linkage. Located in a rural area, Erlin has limited access to home-based palliative services, hospital beds, and hospice physicians. As a result, even when residents reach the terminal stage, timely medical support is often unavailable.

"When a resident dies without being officially enrolled in a hospice program, hospitals cannot issue a death certificate. The institution is then forced to involve the police for administrative verification or call in a local health center physician at short notice to issue the certificate," Kuo explained. These complex procedures not only add stress to staff but also compel grieving families to navigate bureaucratic hurdles at a difficult time.

Legal responsibility poses an additional challenge. Kuo elaborated: if a resident experiences sudden massive bleeding, should caregivers perform CPR, even if it only prolongs suffering? Institutions must conduct multiple family meetings, obtain signed Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) consent, and secure physicians' documentation before they can safely "accompany without intervention."

"We care and we pray," Kuo admitted. "Delivering palliative care in a residential setting is never easy, but our faith gives us strength. Out of compassion and familiarity, we choose not to send residents to unfamiliar hospital wards, but to let them remain with those they know well." and heritage to create a sustainable path for rural communities.

Faith-Based Grief Support

At Erlin Happy Christian Home, palliative care is not only about caring for those who are dying, but also about supporting those who remain. When a resident passes away, the institution holds memorial and comfort services where peers sing hymns and share memories. These rituals serve both as grief counseling and as gentle education about death.

"We don't shy away from talking about death," emphasized Superintendent Esther Lin. Residents openly discuss death and heaven, and come to understand that departure and passing away are not something to fear. For peers with especially deep emotional bonds, social workers and pastors provide one-on-one support to help them through their grief. This approach not only helps residents gradually come to terms with death, but also enables staff, through each farewell, to find the strength to continue accompanying others on the next stage of their journey.

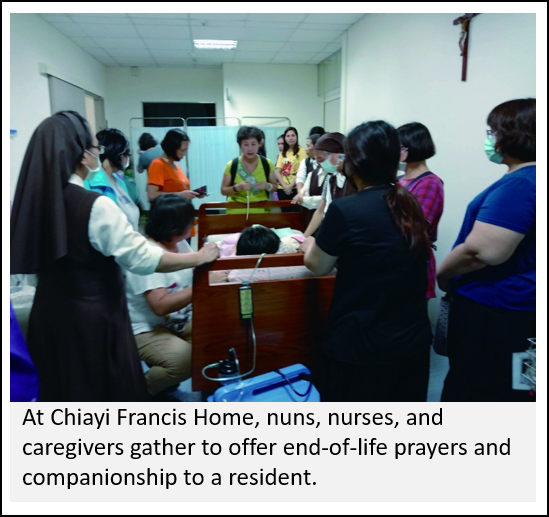

Chiayi Francis Home places equal care in grief support. When a resident reaches their final moments, nuns, nurses, and caregivers gather at the bedside, praying softly and singing until the heartbeat slowly comes to rest. Afterwards, residents living on the same floor line the corridor to see their friend off. In the days that follow, memorial gatherings and annual remembrance services, led by the nuns, continue the process of healing.

"Farewell rituals are also a form of grief counseling," Tsou believes that only by remembering and honoring can death become a shared journey rather than a hidden taboo.

Returning Palliative Care to the Essence of Life

Whether at Chiayi Francis Home or Erlin Happy Christian Home, the journey of palliative care has been difficult, yet steadfast. Without strong medical backing, they rely on interdisciplinary teamwork and faith to sustain one another. In the absence of clear legal protections, they build understanding and trust through repeated dialogue and careful coordination. This challenging yet deeply compassionate path is taken for one purpose: to fulfill the vision that people with intellectual disabilities may "grow old and pass away at home."

This is not only a display of courage by two institutions but also a shared responsibility for society as a whole, because every life deserves to be respected and accompanied until the very last moment. Along the way, these homes carry the weight of limited medical resources and systemic gaps, yet through each farewell they also discover the deeper meaning of life education: death is no longer a forbidden topic, but an invitation to learn, to accompany, and to grow.

"This is their home. We can't bear to send them away." These simple words capture the shared conviction of both Francis Home and Erlin Happy Christian Home. It expresses a hope that palliative care will not remain a privilege for the few, but a right for all—and the most peaceful resting place for every life.