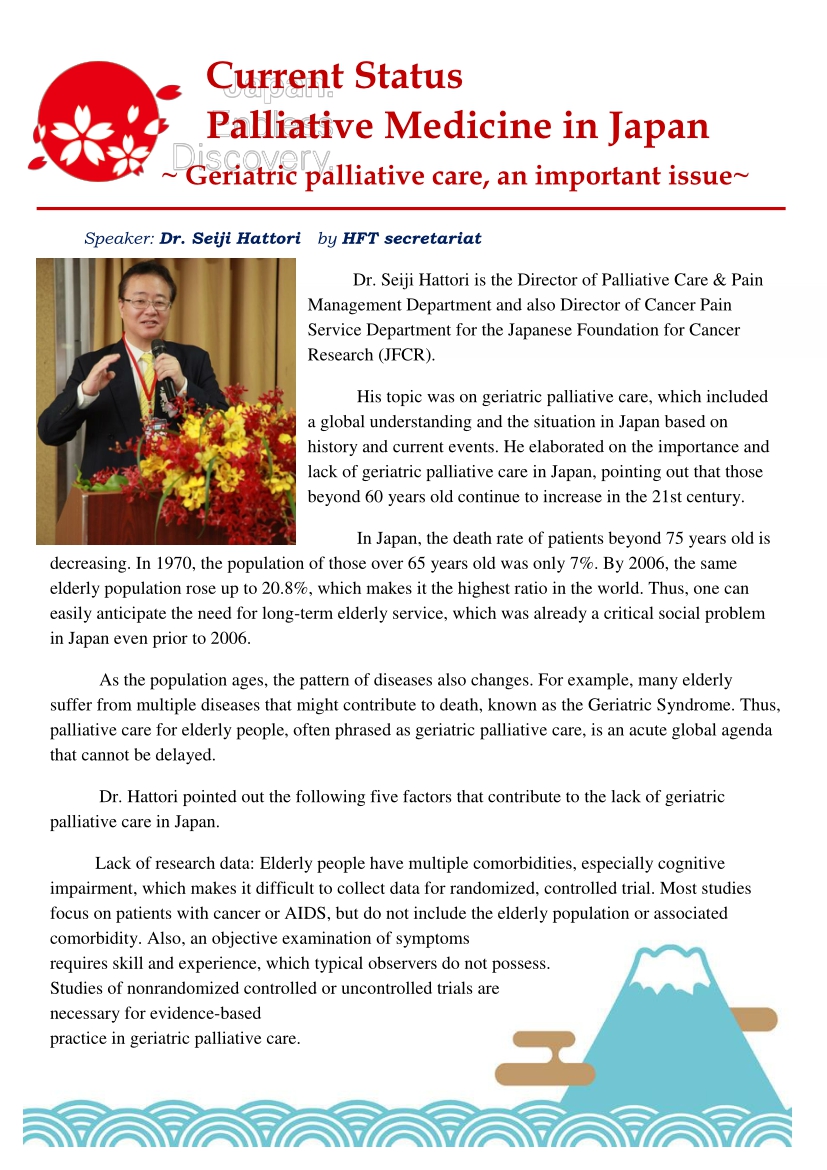

Dr. Seiji Hattori is the Director of Palliative Care & Pain Management Department and also Director of Cancer Pain Service Department for the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (JFCR).

His topic was on geriatric palliative care, which included a global understanding and the situation in Japan based on history and current events. He elaborated on the importance and lack of geriatric palliative care in Japan, pointing out that those beyond 60 years old continue to increase in the 21st century.

In Japan, the death rate of patients beyond 75 years old is decreasing. In 1970, the population of those over 65 years old was only 7%. By 2006, the same elderly population rose up to 20.8%, which makes it the highest ratio in the world. Thus, one can easily anticipate the need for long-term elderly service, which was already a critical social problem in Japan even prior to 2006.

As the population ages, the pattern of diseases also changes. For example, many elderly suffer from multiple diseases that might contribute to death, known as the Geriatric Syndrome. Thus, palliative care for elderly people, often phrased as geriatric palliative care, is an acute global agenda that cannot be delayed.

Dr. Hattori pointed out the following five factors that contribute to the lack of geriatric palliative care in Japan.

Lack of research data: Elderly people have multiple comorbidities, especially cognitive impairment, which makes it difficult to collect data for randomized, controlled trial. Most studies focus on patients with cancer or AIDS, but do not include the elderly population or associated comorbidity. Also, an objective examination of symptoms requires skill and experience, which typical observers do not possess. Studies of nonrandomized controlled or uncontrolled trials are necessary for evidence-based practice in geriatric palliative care.

Education to caregiver and medical professions: The majority of health care professionals receive insufficient specialized training in the care of terminally ill patients. For example, Japanese postgraduate training programs in palliative care is a two-day course focused only on cancer symptom management and communication skills, but not geriatric palliative care or end-of-life care.

Education for family caregivers is also important. The family members, and in fact, everyone in the country, need to know how and where to seek care. Government oversight and public announcements are needed for people to know how and where they can consult for care.

Underassessment resulting in under-treatment: Elderly people tend to underreport their symptoms, leading to under-treatment. Especially in Japan, the elderly try to bear the pain with patience instead of informing their family about their symptoms. Cognitive impairment can also contribute to poor symptom reporting and management. In addition, even when assessment is appropriately done, physicians tend not to give pain medications, such as opioids, to the elderly for fear of side effects (with the exception of cancer patients).

Palliative care society focusing mainly in cancer: In 2006, the Cancer Control Act was approved after a politician shared his cancer treatment experience and demanded better treatment including for palliative care. It was a good advertisement for cancer palliative care. One of the overall goals as stated in the Act was “reduction of burden among all cancer patients and their families and improvement of quality of life.” One of the three priorities, surprisingly, is to “initiate palliative care from the beginning of the therapy.” This is not yet satisfactorily done in actual clinical practice because it would be hard for patients to accept treatment and palliative care at the same time.

Many people became aware of palliative care but only as it concerned cancer. It even became mandatory for cancer hospitals to include palliative care teams. Unfortunately, Japanese Palliative Society does not yet address geriatrics or chronic diseases, and for the government, cancer palliative care is much easier to provide compared to geriatric palliative care since cancer is shorter term and more predictable.

Dr. Hattori shared his thought that the Geriatrics Society is doing a very good job. In 2001, they released a position statement regarding palliative care for the elderly. It consists of thirteen statements to provide the elderly and their families the support they need for optimal care at the end of their lives, with respect to their value, philosophy, and faith. The society equates “palliative care” as synonymous to “end of life care” or “terminal care,” which is much more realistic.

Social support problem: The population is aging but social supports are not sufficient. About 80% of the Japanese elderly currently die in the hospital, but it seems best for patients to return home and receive home care services. Unfortunately, there are not enough workers or home caregivers, which is a big problem in Japan.

Many caregivers have emotional, physical, and financial stress. From 2010-2016, 183 people were killed by their caregivers in Japan due to lack of love and hope. If they had more social or psychological support, or had placements in long-term care facilities, tragedy could have been avoided. Thus, social services need to provide support to the elderly patients and their families, which would require a combination of government act, financial support, insurance, construction, public service, and law enforcement.