As Taiwan gradually enters a super-aged society, long-term care has become an urgent challenge. In rural areas, where resources are scarce, caring for elders is even more difficult. Plahan has chosen a different path: through the idea of symbiosis, it not only provides long-term care services but also integrates community economy, culture, and human connection. This allows elders to age with dignity on familiar land—igniting the way for sustainable elder care in rural Taiwan.

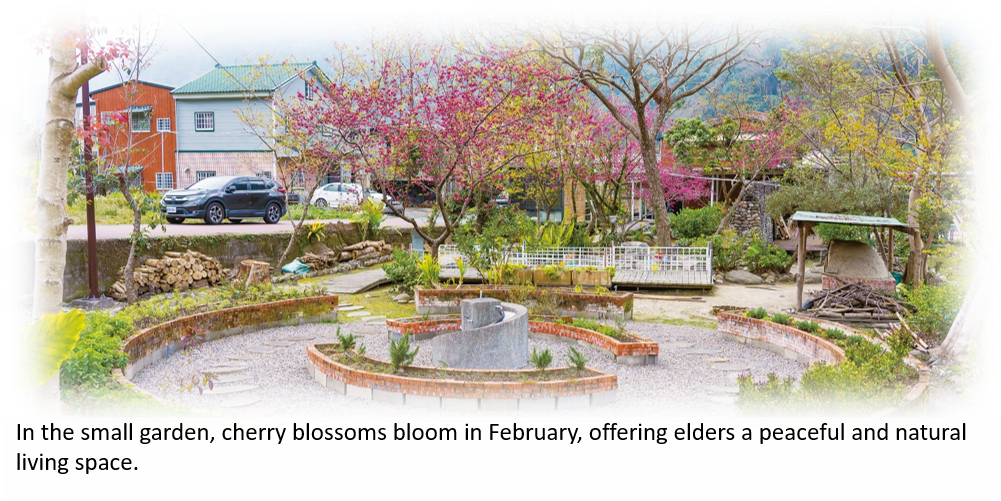

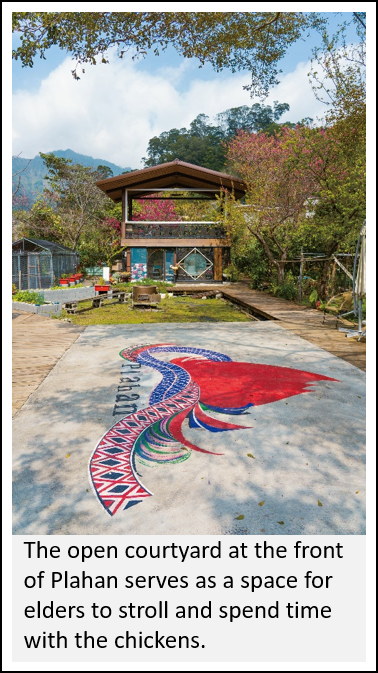

At ten o'clock in the morning, in the Daguan community along the Daan River in Taichung, some elders sit together in a courtyard, enjoying the sun while chickens peck leisurely at their feet. This is not a traditional nursing facility but a place for living and belonging: the Plahan Symbiosis Care Labor Cooperative (hereafter "Plahan").

At ten o'clock in the morning, in the Daguan community along the Daan River in Taichung, some elders sit together in a courtyard, enjoying the sun while chickens peck leisurely at their feet. This is not a traditional nursing facility but a place for living and belonging: the Plahan Symbiosis Care Labor Cooperative (hereafter "Plahan").

Unlike conventional long-term care centers, Plahan does not operate on strict timetables. Instead, elders follow the natural rhythm of tribal life—collecting eggs, planting herbs like mint, or helping with small daily tasks. Through these everyday activities, elders receive restorative care that helps them return to a life of being fully human.

This is a social experiment centered on symbiosis—integrating local labor, culture, and economic resources. It not only provides care but also reimagines the future of rural communities.

All-in-One Symbiotic Care: Aging at Home with Dignity

In 2019, after completing her service as Deputy Mayor of Taichung City, Yi-Ying Lin stepped into frontline work as a home care aide. While training and serving in Heping District, she saw firsthand the shortage of care resources in Indigenous communities. She decided to stay and develop a model of symbiotic care.

Unlike traditional institutions that work in isolation, Plahan emphasizes cross-disciplinary teamwork—nurses, doctors, and caregivers forming a unit. "We coordinate with hospitals before elders are discharged—covering medication, nutrition, wound care, and even home environment planning—so that every step is seamlessly connected and elders can transition back home smoothly."

Lin describes this "All-in-One" approach as a well-trained special forces team. Tailored care plans are designed for each elder, with caregivers rotating in 24-hour shifts. Through short-term intensive care, even critically ill elders can be weaned off feeding tubes, catheters, or tracheostomy tubes—freeing them from long-term bed confinement and returning to normalcy.

One of the most remarkable cases is Grandpa Boshan. Once bedridden and dependent on a feeding tube, he regained his independence in just over a month. With the team's support, he was able to eat, speak, and attend church again. His transformation moved his family and renewed hope within the whole community.

However, Lin admits, "Round-the-clock care is often too expensive for ordinary families." To solve this, Plahan established a time-bank system—volunteers and caregivers can deposit their service hours and later withdraw them when they or their family members need care. This reduces financial burden and strengthens community mutual aid.

Today, Lin's phone is filled with active LINE groups. "Families stay connected to their elders' health updates in real time, and even those living far away can video call to say goodbye with love and dignity."

Today, Lin's phone is filled with active LINE groups. "Families stay connected to their elders' health updates in real time, and even those living far away can video call to say goodbye with love and dignity."

Returning Home to Write the Final Chapter

For elders, home is the safest haven. Plahan actively promotes community-based palliative care, enabling elders to spend their final journey in familiar surroundings. "In Indigenous communities, death is not taboo—it is part of life."

Lin believes culture is the root for community elders. This is why Plahan integrates cultural elements into long-term care, helping elders find renewed strength in their own traditions. For example, the Atayal and Paiwan practice of squatting burials reinforces a sense of family and community connection at the end of life. Elders are also encouraged to join in festivals, songs, dances, or even feed chickens—ordinary activities that restore dignity and a sense of accomplishment.

practice of squatting burials reinforces a sense of family and community connection at the end of life. Elders are also encouraged to join in festivals, songs, dances, or even feed chickens—ordinary activities that restore dignity and a sense of accomplishment.

"Cultural care isn’t a formality," Lin emphasizes. "It is care that reaches into the elders' hearts—making them feel that here, they are not just being cared for, but truly at ease and respected."

A Cooperative Model for Sustainable Long-Term Care

One of the greatest challenges for rural long-term care is the lack of resources. Plahan's solution is to strengthen community power through a cooperative model.

Having studied in the Department of Cooperative Economics and Social Enterprises in university, Lin knew that a cooperative was the most effective way for a community to achieve self-sufficiency. "I may not always live here in the community, so for the village to sustain itself, the cooperative is the best approach," she explained.

Unlike the profit-sharing model of the home-care market, a cooperative emphasizes shared ownership and governance. Every community member is a shareholder, and surplus earnings are distributed based on labor contributed, not social status. "Through economic mutual aid, long-term care services can become a sustainable business while also creating more jobs within the community."

One Egg, Many Hopes for the Community

Beyond its core long-term care services, Plahan developed Friendly Chicken Life, a program designed to help both elders living alone and young people returning home to achieve economic independence. By raising egg-laying hens and selling farm products, elders regain financial autonomy while bringing new vitality to the community.

In fact, Friendly Chicken Life is not just an industry—it's also a model of care. Huan-Ching Yang, known affectionately as the Chicken Principal, explained: "Raising chickens gives elders a sense of purpose. Feeding them, collecting eggs, or simply keeping them company are all forms of rehabilitative practice. Elders also build companionship through the shared experience of raising chickens." The program promotes environment-friendly farming that protects nature, provides healthier eggs for consumers, and generates income for caregivers—creating a virtuous cycle.

Plahan has even woven chickens into community services and events. Initiatives include a chicken leash project where chickens help with weeding while keeping the elders company, as well as Taiwan's only chicken racetrack and the unique Plahan Chicken Sports Games. These events bring joy to the community, strengthen bonds between elders and animals, and brighten daily life with play and laughter.

Extending Love through Community-Based Palliative Care

Plahan's vision has expanded beyond its Symbiosis Care Base. In Shuangqi, it built Taiwan's first Two-Line Poetry daycare center, and it is developing a Share House modeled after Japan's HHM Kasan’s House. This Share House will feature a hostel for visiting caregivers to train and work, while also offering after-school programs for children and co-living spaces for elders. At the same time, Lin is working to integrate community-based palliative care into Plahan’s services, ensuring that elders receive proper medical support and spiritual comfort in their own homes.

"Our goal is to help elders complete life's final journey with peace and dignity," Lin said. Even during her time as Deputy Mayor, she had recognized the urgent care needs of elders in remote mountain and island communities. For years, she has promoted mutual-aid home care models for critical patients and has advocated reforming Taiwan's fee-for-service long-term care system into a "bundled payment" model based on individuals rather than hours in an effort to address the real pain points for families.

As Taiwan moves into a super-aged future, Plahan is more than a successful care institution—it is a seed of hope, blending elder care with tribal culture, economy, and heritage to create a sustainable path for rural communities.